Spinoza and ‘no platforming’: Enlightenment thinker would have seen it as motivated by ambition rather than fear

Unknown artist via Wikimedia Commons

Beth Lord, University of Aberdeen and Alexander Douglas, University of St Andrews

The recent “no-platforming” of social historian Selina Todd and former Conservative MP Amber Rudd has reignited the debate about protecting free speech in universities. Both had their invited lectures cancelled at the last minute on the grounds of previous public statements with which the organisers disagreed.

Many people have interpreted these acts as hostile behaviour aimed at silencing certain views. But is this primarily about free speech?

The debate about no-platforming and “cancel culture” has largely revolved around free speech and the question of whether it is ever right to deny it. The suggestion is that those who cancel such events want to deny the freedom of speech of individuals who they take to be objectionable.

Most of us surely agree that freedom of speech should sometimes be secondary to considerations of the harm caused by certain forms of speech – so the question is about what kinds of harm offer a legitimate reason to deny someone a public platform. Since people perceive harm in many different ways, this question is particularly difficult to resolve.

But perhaps the organisers who cancelled these events were not motivated by the desire to deny freedom of speech at all. Todd and Rudd are prominent people in positions of authority – so cancelling their events, while causing a public splash, is unlikely to dent their freedom to speak on these or other issues at other times and in different forums.

Read more:

Two arguments to help decide whether to ‘cancel’ someone and their work

But these acts have a significant effect on others, who may feel unable to speak on certain issues from fear of similar treatment. Perhaps the no-platformers cancelled Todd and Rudd, not because they wanted to deny them their freedom to speak, but because they didn’t want to listen to them. Perhaps they were motivated not by a rational consideration of potential harm, but by an emotion: the desire not to listen to something with which they disagree.

Ambitious mind

The 17th-century Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza has a name for this emotion: ambition. Nowadays we think of ambition as the desire to succeed in one’s career. But in the 17th century, ambition was recognised to be a far more pernicious – and far more political – emotion. As Spinoza wrote in his Ethics (1677), ambition is the desire that everyone should feel the way I do:

Each of us strives, so far as he can, that everyone should love what he loves, and hate what he hates… Each of us, by his nature, wants the others to live according to his temperament; when all alike want this, they are alike an obstacle to one another.

Spinoza sees the emotions, or “passions”, as naturally arising from our interactions with one another and the world. We strive to do things that make us feel joy – an increase in our power to exist and flourish – and we strive to avoid things that make us feel sad or cause a decrease in our power.

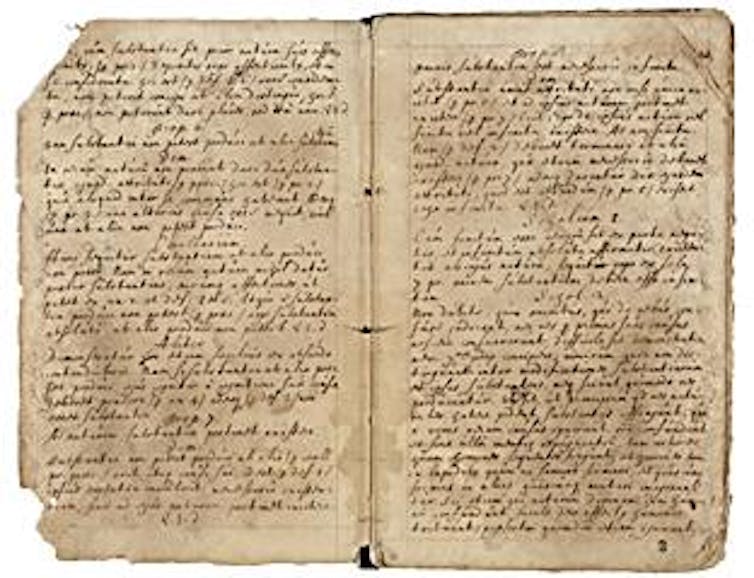

Biblioteca Vaticana

We naturally desire and love what we believe others desire and love. It is therefore natural that we want others to love what we do and think what we think. For if others admire and approve of our actions and feelings, then we will feel a greater pleasure – with a concomitant increase of power – in ourselves.

Ambition is not simply wanting to feel esteemed – it is wanting others to love and hate exactly what we love and hate. It is the desire to cause others to think and feel exactly as we do. It is the desire to “avert from ourselves” those who cannot be convinced to do so – for those dissenters diminish our sense of self-worth.

Disagreement a threat

Spinoza would have recognised the desire not to listen to dissenting views as a species of ambition. Disagreement is perceived not as a reasoned difference of views, but as a threat: something that causes sadness and a diminishing of one’s power – something to be avoided at all costs.

Somebody who feels differently threatens our sense of the worthiness of our own feelings, causing a type of sadness. Spinoza stresses that we strive to “destroy” whatever we imagine will lead to sadness. Thus ambition leads to a desire to change people’s views, often through hostile, exclusionary, destructive behaviours.

Not only that, but someone in the grip of ambition is likely to be immune to rational argument. Spinoza argues that passions are obstructive to good thinking: reason – on its own – has little power to shift a passion that has a strong hold on us.

Most of us have had negative experiences on social media with people who disagree with us on politically charged questions. Instead of engaging with our arguments, they point out that we are immoral or unfeeling for holding a different view. Really, what our opponents find intolerable is our failure to feel the same about the issue as they do.

Refusing to hear an argument and seeking to silence it is a mild form of no-platforming, motivated not by the desire to quash free speech, but by ambition. Our failure to share in the political feelings of others leads them to experience a loss of power, and they respond by attacking the cause of the loss. Ambition makes rational debate impossible, even when our freedom to speak remains perfectly intact.![]()

Beth Lord, Professor of Philosophy, University of Aberdeen and Alexander Douglas, Lecturer in Philosophy, University of St Andrews

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.